harold hedd

harold hedd

Georgia Straight – Last Gasp – Kitchen Sink 1972-84

Harold Hedd. Hedd was the penultimate Canadian hippie hero in Vancouver, appearing in the weekly underground newspaper The Georgia Straight from 1971 to ’73. Hedd also starred in his own comic book titles; two from the ’70s and two from the ’80s, all of which are reviewed here. All four of the books are remarkable and I don’t need to apologize for giving every one of them perfect scores.

Holmes was born in a small town in Nova Scotia but grew up in Edmonton, Alberta, where he worked as a sign painter in a print shop. On the side, he developed a comic strip for a local hot rod magazine and in 1964 he sold a couple of spot cartoons to Help! magazine. In 1965, Holmes did some work for Pete Millar’s Rod & Custom magazine while vacationing in Los Angeles, but his cartooning jobs were irregular. In fact, he stopped doing cartoons altogether for a period in the mid ’60s.

But the advent of the hippie culture in the mid ’60s had a big impact on Holmes. After his brother turned him on to psychedelic drugs in 1968, Holmes left his wife and job in Edmonton and relocated to Vancouver, where he moved into a communal house, grew his hair down to his ass, and lived a non-stop hippie lifestyle for about a year. As he related to Patrick Rosenkranz in Rebel Visions, Holmes “…was experimenting with grass and acid, going to rock concerts, spending all night on the local beaches drifting from campfire to campfire, the whole beach tripping on acid — a wonderful magical time.”

During this magical time, Holmes also began drawing again, which led to a fortuitous event that changed the course of his life once again. In 1970, one of the women Holmes was living with got a part-time job at The Georgia Straight. During a staff meeting (which were very informal), somebody at the Straight suggested they should have a comic strip like the Freak Brothers, and the woman piped up, “I know a guy who can draw where I live.” Holmes had sold one other “non-Hedd” strip to the Straight in the past, but he only got $10 for it. After bringing in his first Harold Hedd strip, the Straight offered him $25 a week to keep ’em coming. The money sucked, but Holmes loved the editorial freedom, so between May of ’71 and April of ’72, there was a new Hedd strip almost every week. Harold Hedd became the everyman hero of the emerging counterculture in Vancouver, which was just as ladled with drugs, free love and hippie shenanigans as the counterculture in the U.S.

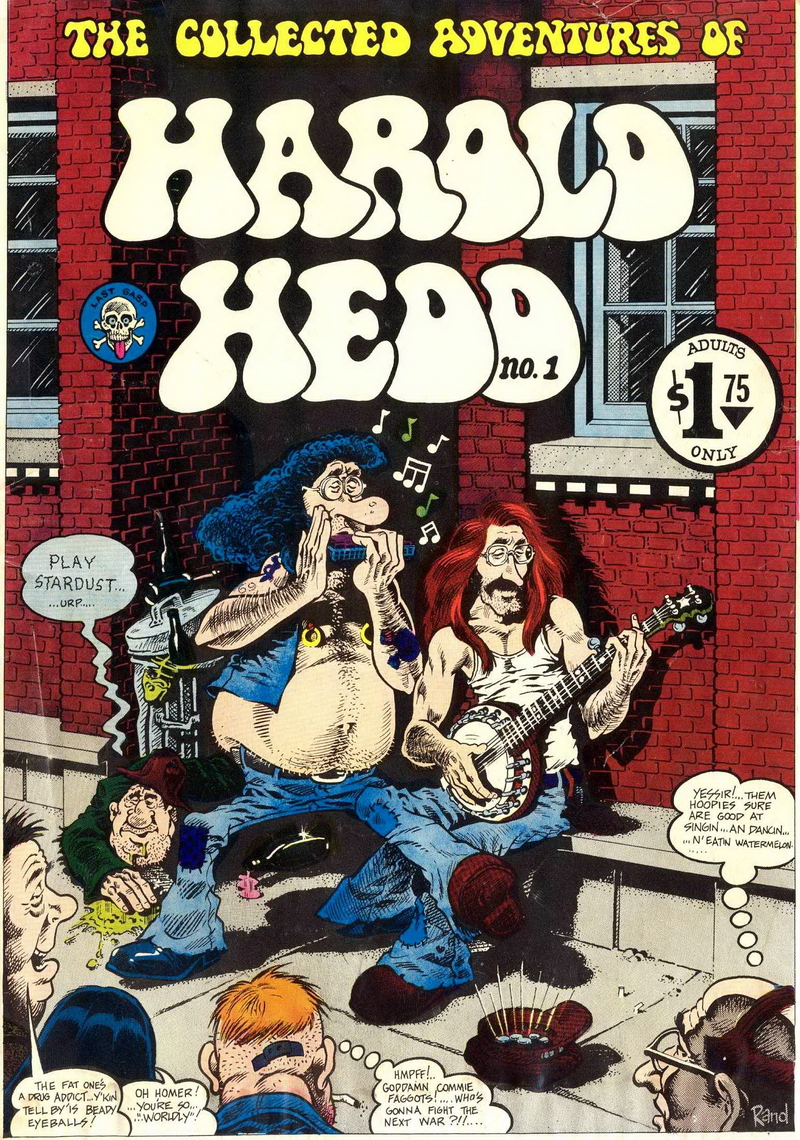

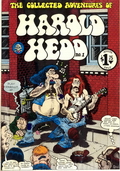

Harold Hedd’s character and his stories are explored in greater detail in the reviews of the individual comic books, but the weekly strips made The Georgia Straight even more popular than before. In fact, when the publishers realized just how popular Harold Hedd was, they doubled Holmes’ fee to $50 a week, which was just enough for the frugal Holmes to live on. In 1972, the Straight published a compilation of strips in The Collected Adventures of Harold Hedd, which sold well in Canada and across the border. This led to Holmes moving down to San Francisco in 1973 with the complete artwork for Harold Hedd #2. Holmes had always felt a kindred spirit with the other underground comic creators, and felt it was time to end his physical isolation from his brethren.

In September of that year, Last Gasp reprinted The Collected Adventures and published Harold Hedd #2, and both books would be reprinted many times in the next 20+ years. However, according to Holmes, his relationship with Ron Turner and Last Gasp did not go so well.

Holmes reported to Rosenkranz that when Last Gasp didn’t pay him his royalties for the second issue of Harold Hedd for six months, he gave up and moved back to Canada in 1974. “The incident sort of took the heart out of me,” Holmes said. “I lost all trust in publishers in general and just couldn’t get the energy up to do any more books. What was the point? $25 a page was a stipend anyway, and then they couldn’t be bothered to do that.” The amount of effort Holmes poured into every page of his comics certainly made it harder for him to justify working full time in the comic book industry. Though he contributed a couple of stories to Ron Turner’s Slow Death while still living in San Francisco, his output became quite sporadic in the following years.

Which, of course, is a shame. Rand Holmes was an extraordinary illustrator and Canada’s most revolutionary comic book artist. He was also one of those underground artists who truly belonged to the counterculture. But unlike the bold and outgoing hippie Harold Hedd (whose image was fashioned after his own), Holmes was rather quiet and reclusive.

In 1982, Holmes moved to Lasqueti Island, a remote island with unpaved roads and no commercial electricity off the coast of British Columbia. While building a house for himself and his second wife Martha, he kept a small, rustic cabin hidden in old-growth forest, where he retreated on a regular basis. Holmes could live off the land for extended periods of time with nothing but a sack of flour and salt. It was on Lasqueti Island that Holmes finished the last story of Harold Hedd, a terrific two-part adventure called Hitler’s Cocaine, which Kitchen Sink published in 1984. It was some of Holmes best work ever, but it didn’t even sell well enough for a second printing (though I believe it sold a bit better in Europe).

After the relatively meteoric success of Hedd in the ’70s, the low sales of Hitler’s Cocaine must have been a grave disappointment to Holmes. While the rest of the world bull-rushed into the technology of the ’80s and ’90s, abandoning the quaint, peaceful life found through living with nature, Holmes only grew closer to his naturalistic roots. Yet he retained his savage wit and keen eye for satire, honed from years of studying Jack Davis, Will Eisner, Harvey Kurtzman and Wallace Wood (his key influence). In the ’80s, Holmes continued producing comics for Twisted Tales, Alien Worlds, and especially the second volume of Denis Kitchen’s horror anthology Death Rattle.

Rand Holmes spent his last 20 years with his wife Martha on Lasqueti Island with a few hundred equally callused and resilient fellow residents. He largely replaced cartooning with oil painting in his last decade, producing a handful of meticulous paintings. He and a band of other artists built an art center on the island that would house much of his work. In 2002, Holmes passsed away at the age of 60 while being treated for Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. His exceptional legacy lives on in 30+ years of phenomenal writing and artwork.

hh 01

hh 01