short order comix

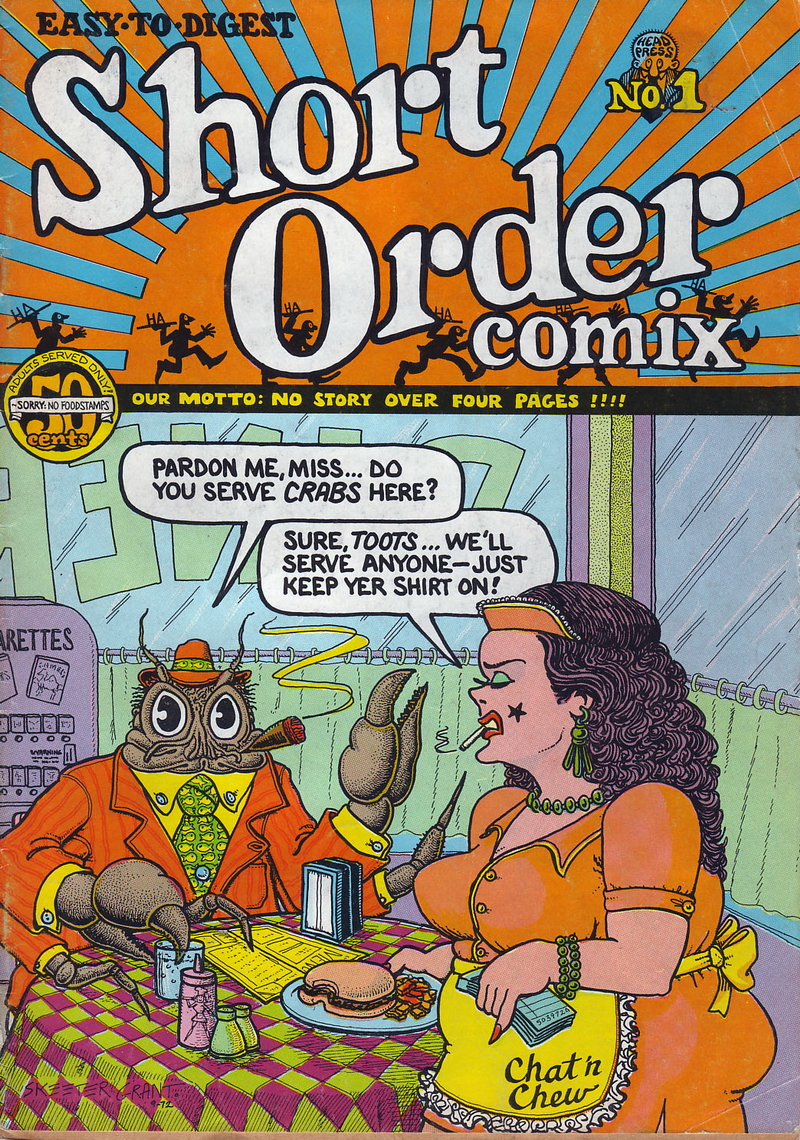

Short Order Comix

Head Press/Family Fun (1973-74)

Short Order Comix is a two-issue anthology edited by Art Spiegelman, featuring plenty of his own work and lots of Bill Griffith and Joe Schenkman, the latter of whom was featured in many East Village Other and Gothic Blimp Works issues. Short Order is an ambitious title with comics that make you think as well as laugh, much like Arcade (which was edited by Art Spiegelman and Bill Griffith) would do a year after this series ended.

Be forewarned, the comics in both issues are often abstract or surreal, dripping with absurd dialogue that I’ve learned to avoid overstudying. Bill Griffith is legendary for his nonsequitur Zippy comics and Zippy makes a smattering of appearances here. Art Spiegelman also delivers some of his most chimerical comics in Short Order, though he occasionally flips a switch for more straightforward stories like “Prisoner On The Hell Planet,” which is about his mother’s suicide, or “Just a Piece o’ Shit,” which features a talking turd.

Several of the comics here would have benefitted from production in a larger format publication (like Spiegelman’s own Raw, which won’t debut for a few more years), because some of the words are so tiny that you almost need a magnifying glass to read them. I sometimes wonder if Schenkman was so used to drawing for underground newspapers that he never adjusted for the much smaller format of underground comic books. In any case, Schenkman does some of his best gritty, urban Schenkman schtick in both issues of this series.

The two issues of Short Order Comix represent one of the earliest of a new, emerging model of underground comix, foretold by Justin Green’s Binky Brown, Guy Colwell’s Inner City Comix, and Mary Wings’ Come Out Comix and flourishing with Arcade and Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor. These are all personal and intellectual comics, not built just for laughs, titillation, gore, drugs, or politics. There had always been some level of intellectualism in the undergrounds, personified by the likes of Beck, Crumb, O’Neill, Stack, Jackson and others, but as their enormous popularity crested, many of the comic artists and writers pursued deeper meaning in their creations.

It is legitimate to declare that underground comix broke new ground and shattered taboos with depictions of sex, drugs and violence. But from the beginning, they became not only the most important comics being published, but the smartest. For the first time, comic art was being aimed directly at adults and not meant to be inclusive of children or teenagers. And after blowing up all those taboos about sex, drugs and violence, underground artists went after the brains of smart adults, challenging their perception of reality and graphic communications.

By 1973, the best mainstream comics were already being influenced by the undergrounds, yet they were still hampered by the ludicrous restrictions of the Comics Code Authority, including that all depictions of recreational drug use be portrayed in a negative light. It would be many more years before mainstream comic creators enjoyed anywhere near the freedoms of underground artists, and even today they are constricted by the fact that their output is marketed to children and teens (not to mention the narrow mindset that defines mainstream publishers).

Even 40 years after its publication, Short Order Comix offers remarkable evidence of the elevation of comic books as an art form. It’s just a shame that Short Order is given such short shrift in the history of comic-book evolution.