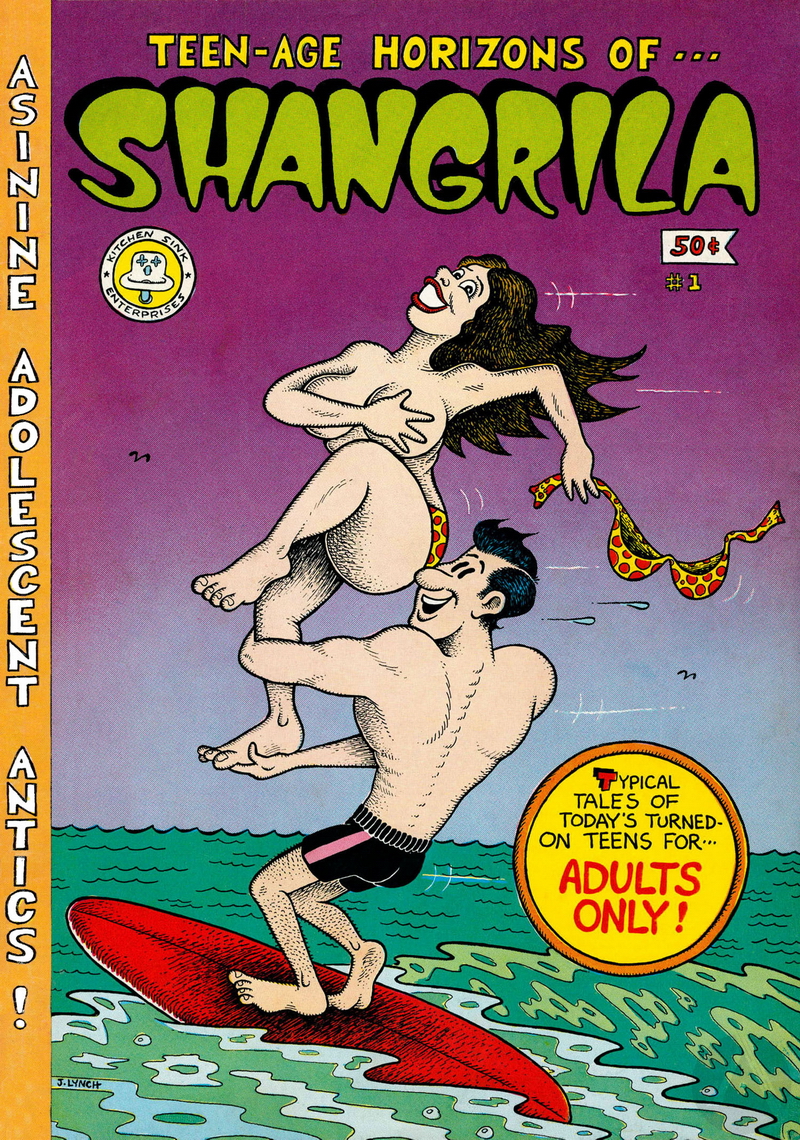

teen horizons of shangri-la

teen horizons of shangri-la

Kitchen Sink (1970-1972).

Teen-Age Horizons of Shangrila became the first comic book anthology series launched by Kitchen Sink. Along with Quagmire, a comic produced by Peter Poplaski and Dale Kuipers, the first issue of Teen-Age Horizons was technically published by Kumquat Productions, a new company Kitchen had formed with the hope of attracting investors. But the rich guy who was initially interested in investing with Kitchen was literally driven away from the opportunity when he read Dan Clyne’s (intentionally) gross “Hungy Chuck Biscuits” story in Teen-Age Horizons #1.

So Kumquat Productions died a quick death, but Kitchen regrouped and launched Krupp Comic Works as an incorporated cooperative with Jim Mitchell and Don Glassford. Krupp’s history is summarized in my reviews of Smile and Mom’s Homemade Comics, but Teen-Age Horizons of Shangrila remains a milestone title in Kitchen Sink’s early history, despite the series being a rather underwhelming anthology.

The first issue features a quintessential Kitchen Sink line-up of artists, including Jay Lynch, Dan Clyne, Justin Green, Jim Mitchell, Don Glassford and Kitchen himself. Glassford was a teaching assistant at the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee and Mitchell was an art student at Marquette University. Clyne was a young cartoonist from Chicago eager to get into undergrounds. Green had been published in Yellow Dog and Gothic Blimp Works and Lynch was already a veteran with Bijou Funnies.

Despite the impressive roster of talent, Teen-Age Horizons of Shangrila #1 is a fairly mundane underground compared to the more daring extremes of the genre. In its first couple years of existence, Kitchen Sink was known for playing it relatively safe, a philosophy that Denis Kitchen acknowledged, and Mom’s Homemade Comics, Quagmire, and Teen-Age Horizons were never designed to match the radical comics found in Zap or the smut digests Snatch and Jiz. But Teen-Age Horizons isn’t just “safe,” it’s also a bit predictable and lacking in original humor, unlike the first issue of Mom’s.

The second issue of Teen-Age Horizons added Richard “Grass” Green, Trina Robbins, Peter Loft and Tim Boxell, but the expanded roster didn’t improve the quality of the content all that much. It almost feels like you’re reading a comic book that is consciously trying to be subversive but doesn’t have the balls to really go there.

But the larger failure may be that the series often portrays teenagers as little more than disgusting, cruel narcissists who couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time. I know, I know, this stereotype isn’t far from the truth for many teens, but here it reminds me of Kitchen Sink’s Dope Comix anthology, which seemed like it would find humor in casual pot-smoking but instead delivered unrelenting anti-drug propaganda while talking down to its audience. Teen-Age Horizons is guilty of the same thing, except instead of being hard on drugs, it’s being hard on teenagers.

That said, there’s certainly some good stuff to be mined from the two issues, including Clyne’s disgusting and morally bankrupt Hungry Chuck Biscuits, Grass Green’s lust-driven escapade in a haunted house, and of course Kitchen’s own story about becoming a hippie. The lack of landmark comics in Teen-Age Horizons of Shangrila makes it a mere footnote in Kitchen Sink’s history, but it remains an important stepping stone to much greater achievements for almost everyone involved with the title.

01 topless surfing

01 topless surfing