#28 Dreams

#28 Dreams

#28 Dreams

Only Printing / Fall 1990 / 52 pages / Rip Off Press

Own Pulled His Float to the Mouth of the Depths to Which he Ascended • So Why I Had that Stupid Dream • Jess’s Dreams • Perils of Counting Sheep in your Sleep or Pulling the Wool over your Thighs • Dream Dream • Why Doesn’t Ice Melt? • Love and Fear • Small Bits of Dreams • Dreams of Paris? • In Dreams • Nacht Merre • Hello There Master of Puppets • Qualms in the Night • Hypnotic Eyes • Nightmare Sublime • Don Donahue’s Dream and More • Ship Dream • Mike’s Dream • Dream and the Dreamer • John Says Goodbye • Bad Spell • Pussy a Good Thing • Once a Huge Hailstorm • Broken Window back cover

#28 Dreams

about this issue

Dreams have always been a fascinating motif in popular art, so it comes as no surprise that dreams would eventually become a central theme for an issue of Rip Off Comix. And so it does with issue #28, which was edited by George Parsons, a fine comics illustrator who later contributed to Rockers, Duplex Illustrated and Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters. Parsons also contributed the front and back cover art for this issue, plus a full-page illustration and a two-page story inside.

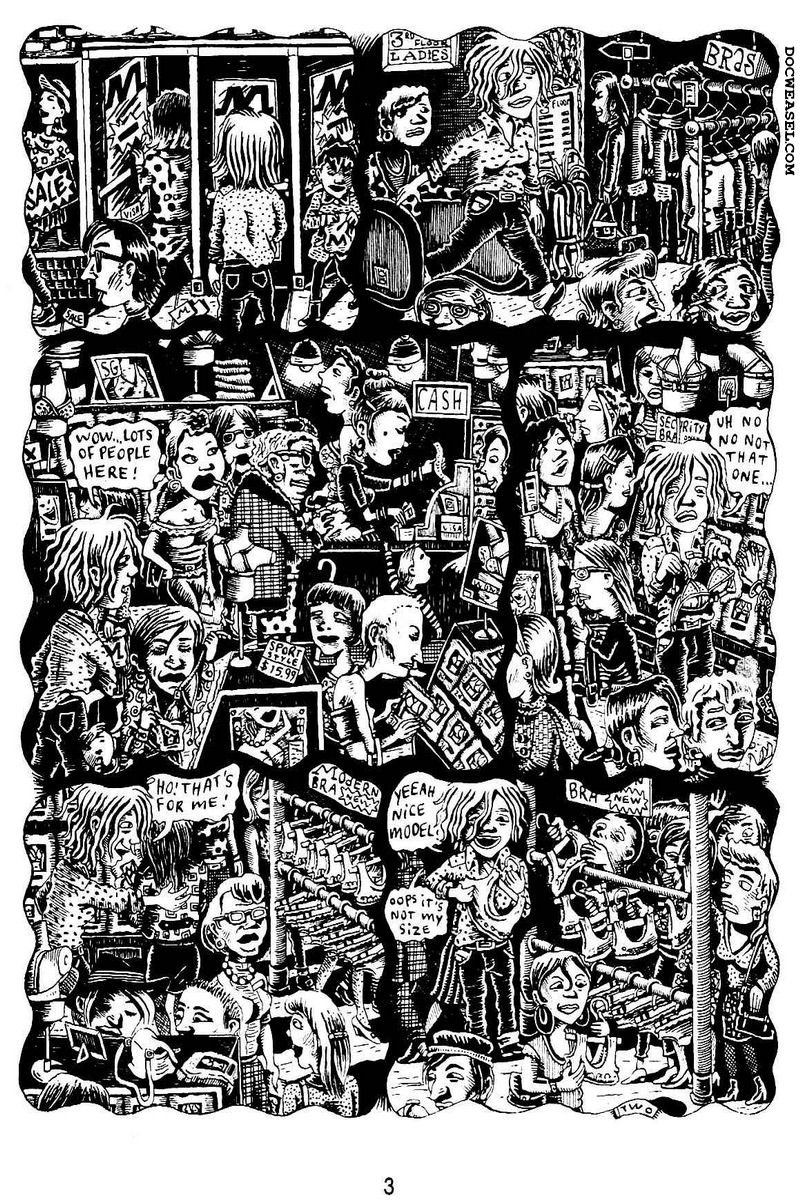

The issue begins with Julie Doucet's three-page autobiographical gem, "So Why I Had That Stupid Dream?" The story opens with a two-panel prologue that reveals a 14-year-old Doucet being hounded by her mother to wear a bra, but Doucet refuses to give in then and continues to go braless as an adult ("My breast is small and solid anyway"). But then she has a dream in which she is "so happy I'm gonna buy myself a bra!"

In a dense series of panels on the next two pages, Doucet goes up to the third floor of a crowded department store and shops for a bra. She finally finds a modern bra that she likes, but the first one she picked out is not her size and then all the modern bras are suddenly sold out, so she doesn't get what she wants. She exits the store all pissed off, only to discover that a nuclear bomb has exploded while she was in the store and the entire city's humanity is dead or dying. Instead of lamenting that tragedy, Doucet thinks "All right! So everybody must be dead too at the ladies section!" She races back to the third floor only to find the entire ladies section is empty. In the final panel, Doucet lies in bed next to her boyfriend, to whom she has apparently described the dream, and wonders "What the Hell does it mean?"

Fuck if I know, Julie, but I think you still have mother issues. "So Why I Had That Stupid Dream?" is a quintessential Doucet strip that fits in nicely with her other comics about strange dreams. The story was reprinted in Twisted Sisters: A Collection of Bad Girl Art (Penguin Books, 1991) and her acclaimed one-woman anthology My Most Secret Desire (Drawn & Quarterly, 1995). Her appearance in this issue of Rip Off Comix was one of her earliest major publications and coincided with her rapid rise in the comics world, leading to the incredibly beautiful eight-year run of Dirty Plotte from Drawn and Quarterly (1991-98).

I still feel bad that Doucet essentially retired from comics over a decade ago and said this in 2006: "I quit comics because I got completely sick of it. I was drawing comics all the time and didn't have the time or energy to do anything else. That got to me in the end. I never made enough money from comics to be able to take a break and do something else. Now I just can't stand comics.... I just don't understand...how you can spend fifty years of your artist life doing the same thing over and over again."

What might appear to be whining strikes me as a tragic reality: Even if you master the art of creating awesome comics, it's entirely likely that you will be lucky to make a truck driver's wage toiling in the "lowly art form of cartoons." Whatever exceptions there might be to that reality, the fact that Julie Doucet quit doing comics before she was 40 because there was no reward in it makes me very sad.

Doucet's story is followed by several effective short stories by Judy Becker, Sharon Rudahl, R.L. Crabb, Robert Kaufman, Bruce Hilvitz, and Dennis Worden, which all convey dreams in a realistic manner. A few pages later, jack-of-all-trades The Pizz presents an extraordinary tale called "Nacht Merre" that portrays a few days in a detox center that culminates in a two-page-spread that flings forth a whirlwind hallucination of lifelong agony. That's followed by a brilliant conquering-a-monster allegory by Richard Johnston, which is followed by two pages of Richard Sala's snippets of nightmares, which is followed by Mario Hernandez's "Nightmare Sublime," which offers an apology to Richard Sala as it documents the grim outcome of listening to an audio recording of subliminal creative thinking, which wreaks terrible nightmares from all who lend an ear to it.

By this time, just over halfway through the magazine, Rip Off Comix #28 has delivered a rat-a-tat-tat assault on our subconscious, giving almost every reader a personal touchpoint to at least one dream state offered within, be it nonsensically bizarre or utterly morbid. Then we turn to the next page and: BAM! the picturesque procession abruptly ends with the nine-point sans-serif text of Don Donahue's one-page "Dream Letters."

One should not give in to the temptation to skip over this simple-looking passage to pursue the next story, which appears so boldly and intriguingly on the opposite page. "Dream Letters" is not about a dream that any of us might relate to, but about a series of dreams and a relationship that are too personal to seem universal. Donahue immediately captivates us with a mere fraction of his first sentence; "About eight years ago, when I was drinking constantly..."

"Dream Letters" contains two letters. The first describes a few weeks of Donahue's experiences while living in a warehouse that was divided into studio living spaces, which served as residences for its artistic occupants. Donahue befriends a female houseguest living temporarily in one of the studios and soon begins a series of dreams about her. He learns that she is also having dreams about him. Their dreams escalate in a parallel pattern until they become so intimate that their sprouting friendship is suddenly shut down by the woman without any explanation.

The plot of "Dream Letters" moves with lightning speed as every paragraph conveys a new chapter. Just a few hundred words seem to convey an entire novel (and indeed a novel could be written from these words). The reply letter (ostensibly from Parsons but signed with the mysterious acronym L.H. R.) that concludes the page incongruously depicts what would seem to be Donahue's near-fatal heart attack. It makes no sense...and yet it seems to make sense.

If Rip Off #28 had ended with Donahue's one-pager, I would have given it an overall score of 10 because it would have been such a perfect culmination to the issue. But it didn't end there. But then I gave it a 10 anyway. Like Deviant Slice #1, I'm willing to give a perfect score when a book is so sublimely wrought for 2/3 of its content.

And like Deviant Slice #1, the remainder of Rip Off #28 still delivers some charms. John Howard's wordless three-pager is untitled in the story but called "The Ship Dream" in the table of contents. It abstractly relays an intense sexual engagement that seems founded on land but fractures into a flaming shipwreck (I think). It's followed by an amusing dream from Erol Otus, a somewhat flat spiritual trance by Mark Wagner, and a pair of realistic dream stories from Mary Fleener and George Parsons.

Rip Off Comix #28 doesn't end quite as strongly as it began, but the "dreams" theme is perhaps the most effectively realized theme in the entire series. This remarkable anthology really began to hit its peak in what would turn out to be its last year of existence.

_

keyline

_

HISTORICAL FOOTNOTES:

It is currently unknown how many copies of this comic book were printed. It has not been reprinted. Like other magazine-format comics with numbered pages, the index of comic creators below follows the page numbers defined in the magazine instead of counting the covers as additional numbered pages.

_

COMIC CREATORS:

George Parsons editor, front cover, 22, 46-47, back cover

John Howard 1

Julie Doucet 2-4

Judy Becker 5

Sharon Rudahl 6-7

R.L. Crabb 8-9

Robert Kaufman 10

Bruce Hilvitz 11-12

Ed Brubaker 13-15

Dennis Worden 16-17

Jaime Hernandez 18 (collaboration)

Gilbert Hernandez 18 (collaboration)

Jonathan Richman 19-21

The "Pizz" 23-25

Daniel Johnston 26-27

Richard Sala 28-29

Mario Hernandez 30-31

Don Donahue 32

John Howard 33-35

Erol Otus 36-39

Mark Wagner 40-43

Mary Fleener 44-47

Steve Lafler 48

Tom Appleton inside back cover