sphinx

sphinx

Last Gasp 1969-73

John Thompson was born in the cozy, beautiful seaside town of Carmel, California in 1945. Even back then, Carmel already had a deep tradition of supporting all aspects of artistic and spiritual expression, and its culture intrigued Thompson so much that he eventually wrote a book of history about his home town (The Secret History of Carmel). Growing up in Carmel had a big effect on Thompson, but his destiny would be found some 100+ miles to the north in the San Francisco Bay area.

In the mid 1960s, Thompson was living on and off in Haight-Ashbury and majoring in art history at the University of California in Berkeley. He painted esoteric subjects in exotic languages on wood panels, printed his own books of etchings, and drew political cartoons for the university newspaper. Thompson experienced first hand the counterculture’s growing discontent with right-wing sociopolitics and appreciated Haight-Ashbury’s free-flowing atmosphere and sense of community. He was a steadfast civil rights and anti-war activist and revelled in the Summer of Love in 1967, when anything and everything seemed possible.

Thompson became a popular creator of psychedelic rock concert posters, many of which were distributed by the Print Mint, so he got to know the owner, Don Schenker, and became friends with other poster artists like Rick Griffin. By 1967 Thompson was contributing comics and cover art to underground newspapers all over the country, and by 1968 he had met Robert Crumb and began contributing to the Print Mint’s Yellow Dog.

It wasn’t long after Zap Comix debuted that Thompson was as prolific in underground comics as he had been in posters. In the summer of 1969, the Print Mint published Thompson’s The Kingdom of Heaven is Within You, which had cameo appearances by more than a dozen artists, authors and poets. By the end of the year the Print Mint had also published Thompson’s one-man books The Book of Raziel and Kukawy Comics. The Book of Raziel is about the Angel Raziel, who authored the original book that was reputed to contain the keys to the mysteries of the universe. Kukawy Comics remains virtually indecipherable, mixing unintelligible symbols with almost-random words that probably only Thompson understood.

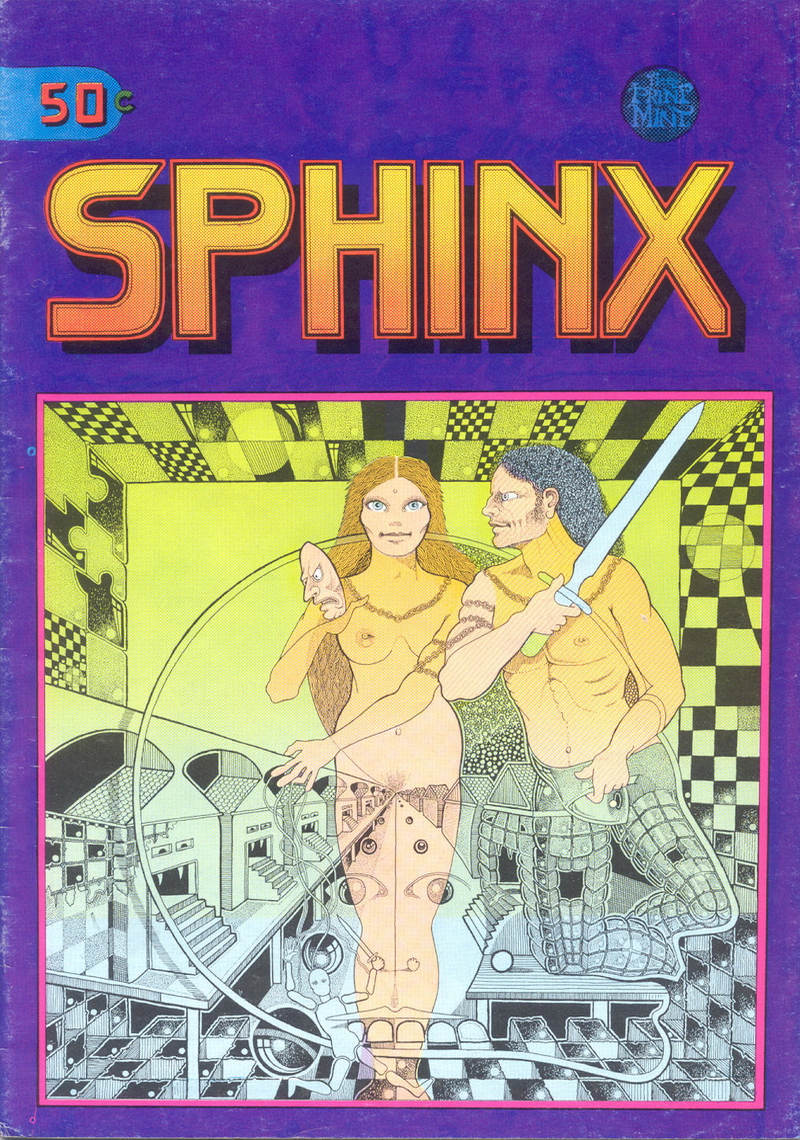

Regardless of the subject matter, Thompson’s exquisitely detailed ink illustrations and sumptuous female figures made his books stand out from an increasingly crowded marketplace of undergrounds. At times, his male and female characters appear as the most graceful symbols in the universe. On other pages his humans integrate with their environment, bending and blending as players in surreal landscapes or cosmic panoramas, yet always remaining the focal point. As comic-book historian and author Dan Nadel wrote wrote of Thompson: “No one else on the undergound scene achieved his kind of aesthetic delicacy.”

Though he was friendly with other underground creators, Thompson was repelled by the grotesque and violent comics of creators like S. Clay Wilson, Rory Hayes and many (less talented) cartoonists. When Crumb began to portray ugly sex and brutality in his comics, Thompson made it clear that he felt such work was degrading to women and detrimental to advancing the art. Thompson wasn’t afraid to depict sex in his comics and he often did, but it was always portrayed as a mutual, harmonious sharing of joy.

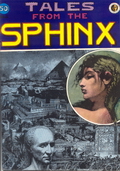

Sphinx Comics was published in 1972, beginning with issue #2. What about the first issue, you may ask? Well, it’s common knowledge to veteran underground comix aficionados that Sphinx #1 was never published. Some might also think it never existed, but it did. What was supposed to be the front cover art was published by Bruce Chrislip on the back cover of City Limits Gazette #6 in 1983, and Michael Roden of Thru Black Holes Comix once had an agreement with Thompson to publish the entire 32 pages of Sphinx #1 in 1985 or so. Unfortunately, the project fizzled out when Roden couldn’t get his local high-school print shop to print the nude images contained in the book.

So we are left with only the final two issues of the series, which I believe mark Thompson’s most amitious work in underground comix. The two books contain essentially one overlapping story about how extraterrestrial visitors invade ancient Egypt and spark a centuries-long battle between good and evil. More details about the plot and characters are provided in the individual book reviews, but really, how much more needs to be said? John Thompson’s comics can be perceived in as many ways as there are types of readers, and defining the scope or meaning of them can say as much about the reader as the content being read.

One can virtually absorb the writing of Thompson’s comics in a single glance and build a perfectly compelling story just by studying the accompanying artwork. As the old saying goes, “a picture paints a thousand words.” Art critic Thomas Albright wrote that Thompson “…creates powerful symbolic images which have the haunting ambiguity and multiplicity of potential meanings.”

Thompson himself understood this ambiguity and the potential meanings: “The viewer as relative evaluator puts the value into these things,” he told Mark James Estren in A History of Underground Comics. “Thus they are mirrors of consciousness. Some folks think they stink. Some folks think they hold great cosmic truth. Some think them obscene. Some are bored. Some are scared. Your reaction to them is relative to your frame of mind. This is obvious.”

Both issues of Sphinx also contain robust sections of Thompson’s superior single-panel illustrations, which are some of the most impressive work produced in comic-book history. They are reason enough to own both books, but when you realize that Thompson put just as much care and effort into illustrating his mystical stories, they become sweet icing on a heavenly cake.