snatch

snatch

Print Mint (1968-1969)

In the summer of 1968, the trailblazing Zap Comix #1 caused many minds to be blown in major cities across America. Somewhere around the end of that summer, the even-more-daring Zap #2 hit the streets and many of those blown minds went into shock. Even some of the counterculture radicals who saw Zap #2 were disgusted by S. Clay Wilson’s depiction of one man cutting off the tip of another man’s penis and eating it. Many were outraged by Robert Crumb’s use of racist imagery to depict a sexually insatiable African junglewoman named Angelfood McSpade.

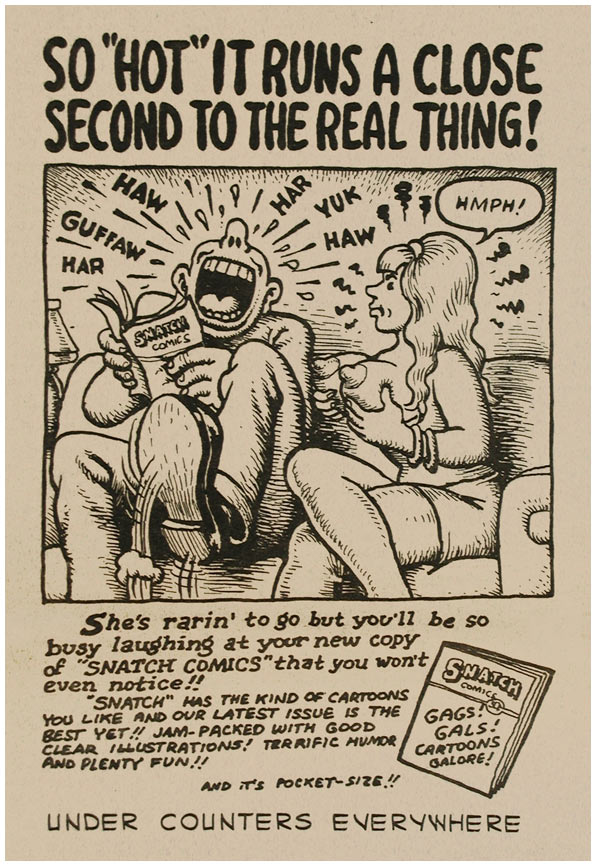

Criticism came fast and hard, and it came from all corners, with outcries from the left and the right that Zap had gone too far. Rather than feeling chastened, Crumb and Wilson decided to demonstrate just how far they could go. Crumb had already been toying with the idea of lampooning the bawdy little joke and cartoon digests that were sold to men on newstands and military bases. As Snatch Comics publisher Don Donahure explained Crumb’s inspiration; “They were just corny little cartoon magazines, pocket-sized. He started doing an imitation of one, only raunchier.”

Wilson, the leading provocateur of the Zap Collective, quickly jumped on board. Crumb and Wilson produced Snatch Comics #1 in just a few weeks and Don Donahue published it in the fall of ’68, though he strategically omitted his Apex Novelties imprint and all copyright information in the book (as well as the two Snatch books to follow).

At 5 by 7 inches, Snatch #1 may have appeared innocuous, but it made up for its diminutive size with explosive content. Nearly every page oozed with depictions of cocks, cunts, boobs and asses of all ages engaging in deviant behavior. Where Zap #1 and #2 were mostly fun-loving hippie comics with a few dashes of kinky behavior, Snatch #1 was wall-to-wall twisted perversion. Crumb and Wilson easily achieved Snatch’s objective to shock to its audience, but also, perhaps unwittingly, unleashed one of the most influential comic books in history.

The first print run of the comic was nearly bought out by Moe’s Books in Berkeley and the book store owner, Moe Moskowitz, reported that he sold 350 copies of Snatch #1 in three days. Unfortunately, he also sold a copy to a Berkeley police officer, who went to the local D.A.’s office and obtained an arrest warrant from a judge. Moskowitz was then arrested in his bookstore on the charge of selling “lewd and obscene material” and police seized several different “obscene” publications, including Zap #2, Horseshit Magazine, Ron Cobb’s Mah Fellow Americans, and gun-wielding feminist Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto.

Moskowitz soon got out on bail and went back to his store, where he commented, “They wanted to get me because of Snatch magazine. But I sold out and they were disappointed when they couldn’t find any copies. So they got me for Horseshit.” Other Berkeley bookstore owners, who were not targeted but also sold Zap, rallied in support of Moskowitz and the charges were eventually dropped after the evidence went missing. But that didn’t end the legal troubles for Zap and Snatch.

Snatch #2 came out in January of 1969 and added Victor Moscoso, Rick Griffin and Rory Hayes to its line-up of artists, though only Hayes made a significant contribution (Moscoso and Griffin had one page each). Hayes had already produced the first issue of Bogeyman in the fall of ’68 and Crumb and Donahue were impressed enough to encourage Hayes to contribute a few smut comics to Snatch #2. With Hayes’ stunted emotional maturity and limited perspective on the subject of sex, the comics he drew for Snatch were permeated with images of naked bodies, severed body parts, exploding blood and other spurting body fluids. Right up Snatch’s alley. Of course, Hayes went on to produce the stunning Cunt Comics later that year, which joined the growing canon of smut comics infiltrating mom-and-apple-pie America.

Moe Moskovitz’s arrest had thrown a scare into Don Donahue. Afraid that he might get busted himself, Donahue began clandestine distribution of Snatch, Cunt and Jiz (also 1969). Advertising for Snatch was rare, but even when it appeared it didn’t point anyone to a particular retailer (see ad on right). Donahue would sell wholesale copies to local hippies and kids who would then sell the books on the streets. “There were a whole bunch of people who used to come and buy copies of Snatch from me and then go down to Haight Street and sell it under their coats,” Donahue reported. “There was one guy who got really rich. There was a girl who used to come every week and buy a couple of hundred copies of Snatch Comics. It was really an underground trip.”

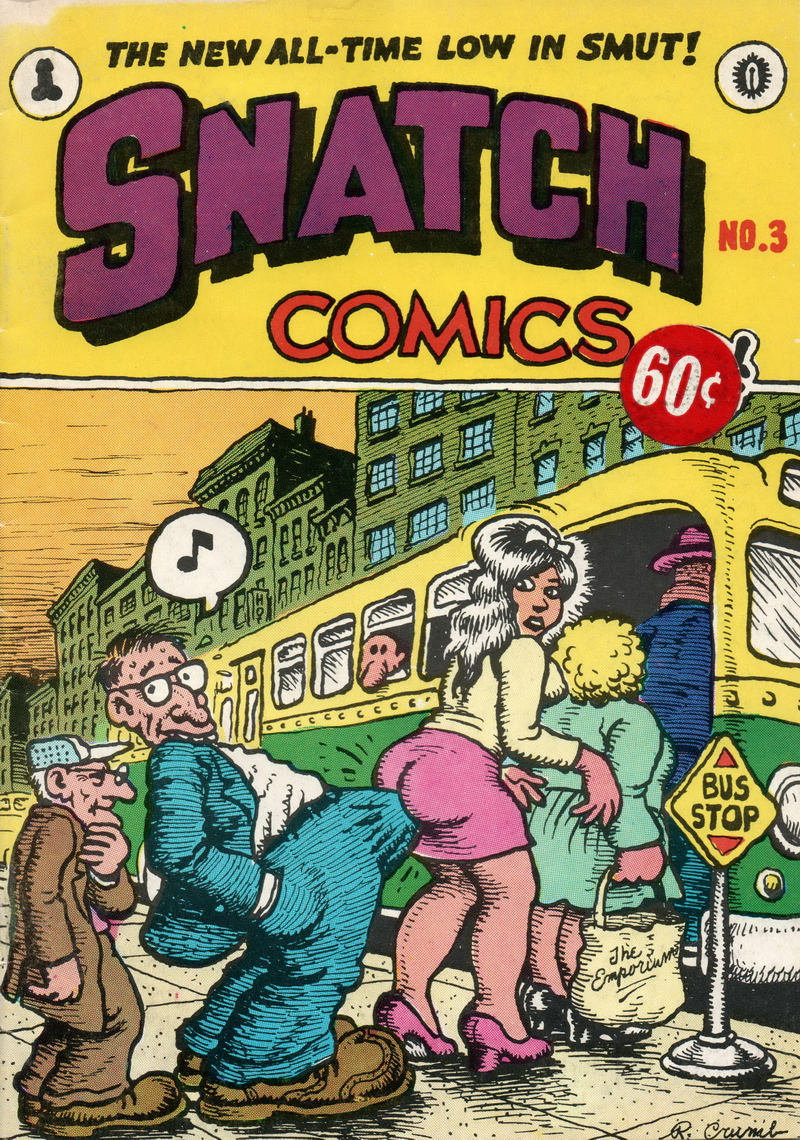

Snatch #3 added Robert Williams and Jim Osborne as contributing artists and came out in the summer of 1969, the same month as Zap #4. The third issue sported the same theme as the first two but didn’t offer quite as much outrageous smut (Zap #4 was more provocative). Snatch #3 turned out to be the last of the series, and brought an end to the flurry of smut comix produced in the previous year. To some degree, the concept had been played out after its point had been made; or, as Crumb surmised, “If taboos were broken by Snatch—groovy! Then we can move on to something else.”

As Robert Williams put it to Patrick Rosenkranz in Rebel Visions, “When we got into those things, we were going for the jugular vein. We were seeing just how absurdly improper you can get before the authorities have to hunt you down. Now you look at it and it’s nothing. It’s nothing now, but boy in the late ’60s and early ’70s that stuff was just really hot potatoes. You just didn’t show those to everybody.”

As it turned out, the authorities would hunt them down one more time. After Snatch #3 and Zap #4 came out, The Phoenix Gallery in Berkeley put on an exhibit of “The New Comix” in October 1969. Si Lowinsky, the gallery owner, displayed original underground art from the Zap Collective and many other underground artists, but the ones involved with the smut comix were reticent to include the original art for Snatch or Jiz for the show. Instead, the gallery simply offered copies of Snatch, Jiz and Cunt for sale. Shortly after the show opened, Berkeley police raided the gallery, seized all the smut comix, and arrested Lowinsky on obscenity charges.

Unlike the Moe Moskowitz arrest, the case against Lowinsky actually went to trial in March 1970. The prosecution relied only on the cops who made the arrests, while the defense called in an expert witness, Peter Selz, the director of UC Berkeley’s art museum. After Selz proved an able witness, the jury carefully reviewed the smut comix and reached a not guilty verdict in about an hour. Lowinsky commented after the trial, “The jury had decided that people have a right to symbolically represent all sorts of outrageous acts, and that society has no right to ban such representations.”

Now in the clear, Snatch and Jiz would end up being reprinted multiple times over the course of the next few years, bringing joy to thousands of children. Or rather, arrested adolescents…. Hmm, perhaps you can come up with an appropriate phrase yourself.

More than any of the other smut comics, Snatch offered something for virtually every deviant as it lampooned incest, necrophilia, orgies, animal sex, pedophilia, S&M and golden showers. “I have this morbid fascination with deviancy, and I like drawing it in comic strips,” said Wilson. “I find it entertaining. I’m sure a shrink would have a field day trying to figure out why I did it. I just find it fun. People can take it or leave it.” As for the publisher who never put his name on the comic books themselves, Donahue believed that they were really producing avant-garde art; “Snatch turned into an art magazine,” he said. “They started with the idea that all the artists were going to do dirty pictures. Then they went wild with their own styles. Snatch turned into a fine arts trip.”

For a “fine arts trip,” Snatch proved to electrify the marketplace, though its success was more cultural than financial. All three issues of the series barely produced a hundred thousand copies, but it was one of the most influential comic books in the industry and blazed a trail for an extensive history of erotic comics that followed in its wake.

As Rosenkranz concluded in the 2011 compilation Snatch Comix Treasury: “Despite all the hubbub and hullabaloo triggered by Snatch Comics, the books ultimately served a social purpose. They loosened restrictions on artistic expression, and inspired other artists to examine their own internal censors. Today just about anything goes in books, magazines, films and video games. Whether that’s a good thing or not is up to each individual to decide.”

I reckon it’s a good thing, Patrick.