MOTOR CITY COMICS

Motor City Comics

Rip-Off Press (1969-1970)_

While underground comics had brought Robert Crumb significant social popularity and financial wealth by 1969, he also endured quite a bit of criticism for the way his comics portrayed chauvinism and outright hostility towards women. After the hyper-smut content of the Snatch and Jiz digests, Crumb said that he hoped the raw porn in those books had broken all the sexual taboos and would subsequently allow cartoonists to move on to something else.

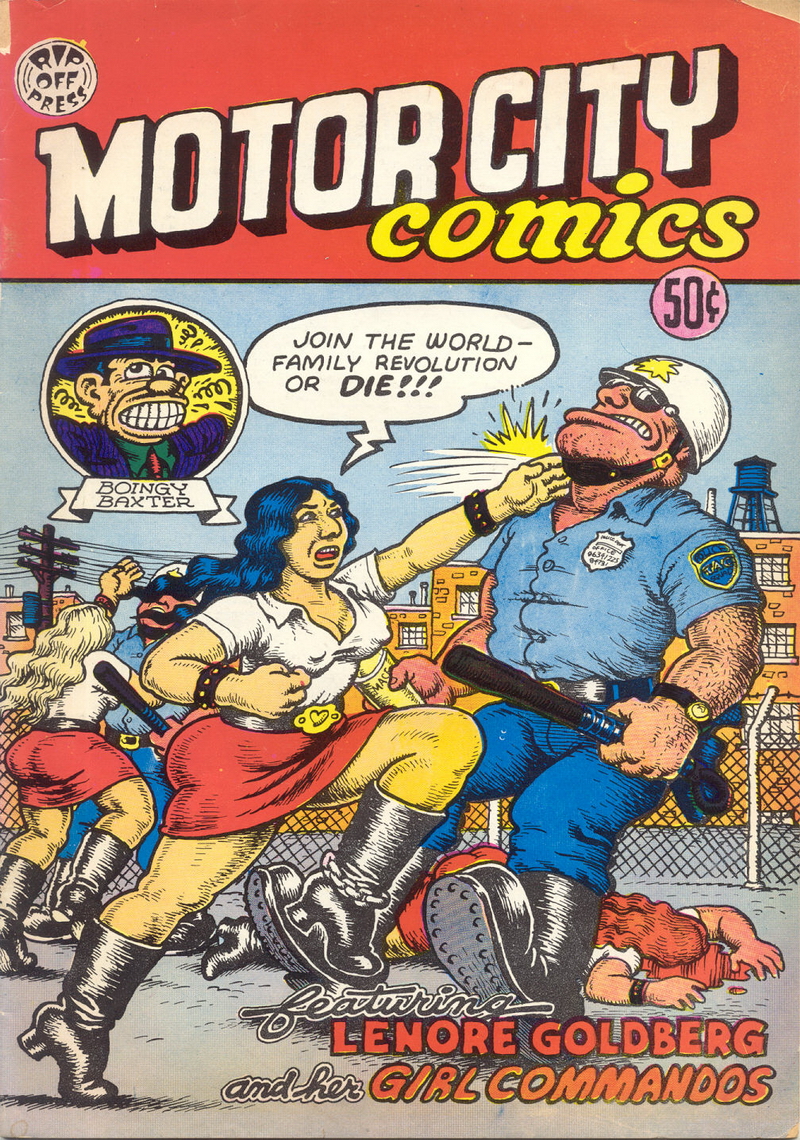

Following that statement, in the spring of 1969 Crumb produced Motor City Comics #1, which introduces Lenore Goldberg, one of his strongest female characters to date. While she displays some of Crumb’s favorite physical attributes, such as muscular thighs and cheesecake cleavage, Goldberg is the most earnest feminist he had yet created.

In the debut issue, Lenore Goldberg is the leader of a group of young women who storm a meeting of liberal intellectuals to “clear the air of all this bullshit about ‘femininity’!” Goldberg declares that “men and women must get together as equals, but for this to happen the whole society must change radically.” She never explains exactly how society must change; instead, Goldberg and her “girl commandos” ridicule the sexually repressed intellectuals by pretending to flirt with and seduce them, but it’s all just a game and they exit the meeting after humbling their enemy.

When Goldberg and the commandos are pursued by police as they flee the meeting, one of them is caught and brutally punished, but this only strengthens their resolve to expand their membership and push the feminist revolution to the next level. Of course, in Crumb’s eyes, the revolution does not prevent Goldberg from giving her boyfriend a blow job the very next day (granted, only after getting orally pleasured herself).

By the time Motor City Comics #2 comes out in 1970, a federal investigative agency is tracking the activities of Goldberg, who now has an arrest record for inciting riots, possession of drugs and firearms, and assaulting an officer, among other things. The agency infiltrates the “women’s liberation front” with a female informant, who exhorts the group to take criminal action at their next protest, but Goldberg, who has learned a few lessons from past mistakes, tempers the idea of violence.

Instead, the group assails a televised beauty pageant and Goldberg takes command of the stage to begin a speech about the exploitation of women, but the riot squad (tipped by the informant) is lying in wait for them. When the cops bust onto the stage, the informant agitates the crowd and a free-for-all breaks out. While trying to escape, Goldberg’s dress is torn off by a cop, but she manages to evade his clutches and outraces the police by running naked through the streets and a grocery store. Despite winning her freedom, the threat of being arrested on sight ends Goldberg’s role as the leader of the girl commandos. Accompanied by her lover and a friend, Goldberg departs for the Canadian wilderness to get a fresh start with a small community of hippies.

A year later, one of Goldberg’s girl commandos tracks her down in Canada, where Goldberg has settled into a new life as the mother of a new-born boy. It appears she’s abandoned her radical politics and accepted a maternal role in a semi-traditional family because, as Goldberg says, “Well, y’know…life goes on an’ things change.”

While many hailed Crumb’s Goldberg character as a feminist role model, others criticized him for what they felt were compromises of Goldberg’s integrity, as if enjoying sex and having a baby precluded her from being a feminist leader. In my opinion, these criticisms have not aged well in the past 40 years, but the social observations contained within the tales of Lenore Goldberg and her girl commandos have held up admirably.

The two-issue series of Motor City Comics features many other comics beyond Lenore Goldberg, including “The Inimitable Boingy Baxter,” “Eggs Ackley in Eyeball Kicks” and “The Simp and the Gimp,” but none of them deliver the tangible personalities or astute insight of the Goldberg stories. In fact, some of the other comics may rank with Crumb’s weakest efforts, particularly in the scripting, which prevents both issues of Motor City Comics from being full-on underground classics.

Nevertheless, the two Goldberg gems elevate these books above the standard fare in Crumb’s early pantheon and, because they are examples of pre-’70 underground comics near their best, are worthwhile additions to any collector’s library.